Profitable Riparian Buffers

Planting trees next to waterways creates the greatest ecosystem impact per dollar spent. These areas are known as riparian zones, critical areas, and streamside management zones. When they are planted with trees and shrubs in addition to grass, they serve three core functions for water quality:

Catch sediment – keep the soil out of the rivers

Absorb runoff – namely nitrogen and phosphorus

Shade the water – fish like cold water, and algae does not.

Dr. Benoit Truax of the Eastern Townships Forest Research Trust walks through a planned riparian buffer he planted 16 years ago to hybrid poplar and native hardwoods. The buffer is extremely effective at catching sediment, absorbing runoff, and shading the stream.

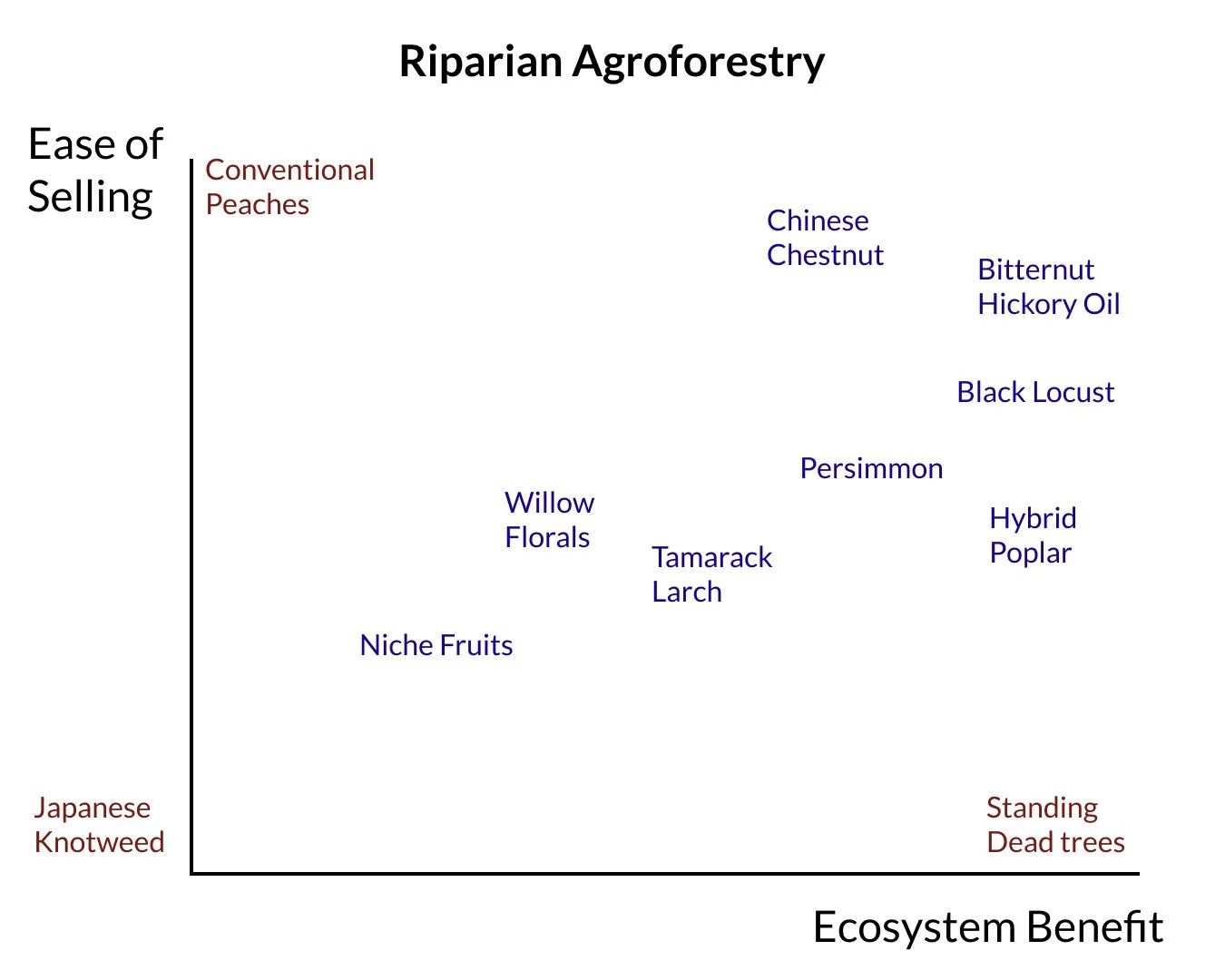

Riparian buffers can be profitable farm enterprises if planned and managed correctly. Engineering these areas to generate income and grow asset value – rather than remain a management cost and liability – will increase their durability and generate economic value across rural America.

Government agencies and NGOs recommend a hands-off approach. One way to conserve nature in these areas is through non-management: leave it alone, don’t touch it, and don’t harvest anything from it. While this is well intentioned, status quo management of many riparian zones consists of the periodic removal of all trees and shrubs. Farmers will rip everything out with an excavator, push it into a pile, and burn it with diesel fuel. This understandably reinforces the idea that production and conservation are inherently at odds.

Profitable agroforestry systems are the best of both worlds. If the trees next to ditches, creeks, streams, rivers, and lakes pay for themselves and then some, land managers are more likely to maintain permanent or semi-permanent tree cover. Large trees that produce high-value products are ideal. Agencies and NGOs introduced the term “working buffers,” in which selected conservation species could theoretically produce some value, namely via the harvest of fruits and berries. Extension agents have historically been confined to highlighting the native tree species that are approved for conservation and also produce something edible: aronia, elderberries, mulberries, persimmons, oaks, and hickories. Yet riparian agroforestry systems can be more than esoteric purple berries – not to discount the immense health benefits of antioxidant-rich native foods.

Riparian Agroforestry Species for Well-drained soil

Riparian zones are not confined to the ostrich ferns growing in the fertile silt of ecologically-vibrant flood plains that tempt farmers to clear them for grain production. The word “riparian” and the word “river” share the same latin prefix. Riparian zones are anything next to water. We often associate stream sides with flat floodplains, but riparian zones can be well drained and never flood. This is especially relevant to farm ditches.

Chinese Chestnut, Castanea mollissima is a nut tree with a strong growth market potential. It grows best in deep, acidic, well-drained soil. This crop is excellent for those interested in marketing and selling nuts to ethnic markets. Adapted to Zones 5-8.

Black Locust, Robinia pseudoacacia is a fast-growing hardwood native to the eastern United States. The tree’s wood is extremely rot-resistant, and it is commonly harvested for fence posts and high-end lumber for decks and docks. Adapted to Zones 4-8.

Lower-input fruit crops: Seaberry, Goumi, Blackcurrant, Elderberry, Asian Pear, and others – Riparian zones often create opportunities for smaller enterprises, rather than economies of scale, given that they are often distributed across a farm, and do not make up the vast majority of any given farm’s acreage. For those interested in value-added fruit, fruits for value-add can be a reasonable option, though they rarely have price floors and require substantial marketing. Adapted to Zones 2-9.

Riparian Agroforestry Species for poorly-drained or flood-prone soil

Bitternut Hickory, Carya cordiformis is a nut tree in same family as pecans, and is native to eastern North America. The nuts it yields are high in tannins, but the tannins are left behind when the nuts are pressed for high-end culinary oil. Adapted to Zones 4-9.

Tamarack Larch, Larix laricina is a slower growing deciduous conifer that tolerates wet soils, and is native to the Northeastern US, northern midwest, and much of Canada. It produces rot-resistant lumber after 40-50 years. Adapted to Zones 2-6.

Hybrid Poplar, Populus spp. is a fast-growing tree that tolerates wet feet, seasonal flooding, and heavy soils. The wood it produces is of lower-quality, but serves its purpose as dimensional lumber for always-dry locations. Poplar excels at absorbing agricultural runoff. The Populus genus also contains cottonwoods and aspens, but this tree is not directly related to tulip poplar, Liriodendron tulipifera. Adapted to Zones 3-9.

Willow, Salix spp is commonly associated with large trees hanging over water, but shrub willows for florals and basketry make for an excellent option in scaled-down riparian plantings. Willows grow quickly and also excel at nutrient uptake. Hundreds of species and varieties are adapted to Zones 3-10.

American Persimmon, Diospyros virginiana produces excellent fruit, and selected varieties can be marketable for fresh eating. Persimmons thrive in flood plains, and can tolerate standing water in the dormant season, though are not suited to perpetually flooded areas. The tree tolerates high-clay soils better than most fruit trees. Adapted to Zones 4-9.

On-farm riparian zones can and should yield marketable farm products. Market goods such as fence posts, lumber, nuts, and fruit can compliment and maintain the public goods (water quality, food mitigation) that riparian buffers create for society. If riparian zones are viewed as acres that create asset value and yield income, rather than liabilities to be resentfully dealt with, farmers and land managers can move beyond an arms-length or adversarial relationship with the agencies and NGOs tasked with managing the quality of the water that runs off of farmland.

Propagate’s mission is to establish agroforestry as a cornerstone of agriculture. Registered as a B Corporation, we have rural economies and ecosystem services written into our charter. We manage over 2,000 acres of agroforestry across New York, Kentucky, and Tennessee. If trees seem a good fit for your farm, farmland, or your network, please don’t hesitate to contact us here at Propagate. We offer:

Land Planning Services: Agroforestry Design and Economics, along with Education for the enthusiasts

Trees for Sale: Sourced from the best genetics the U.S. has to offer

Project Development: Site Preparation and Planting