3 inflationary pressures on farmland prices, and why it may slow regenerative practice adoption

Farmland valuations are the primary basis of equity within agriculture. This makes them the linchpin of any kind of agricultural land use change. When farmland value is viewed through the lens of a new practice, the most important question is how will this affect my land value.

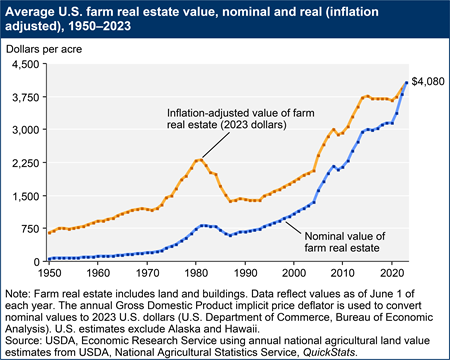

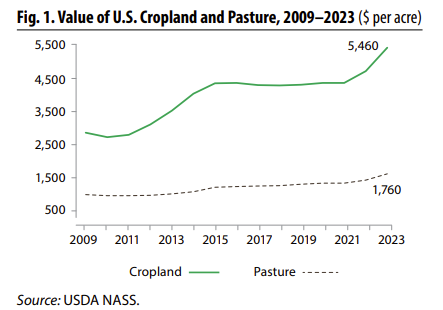

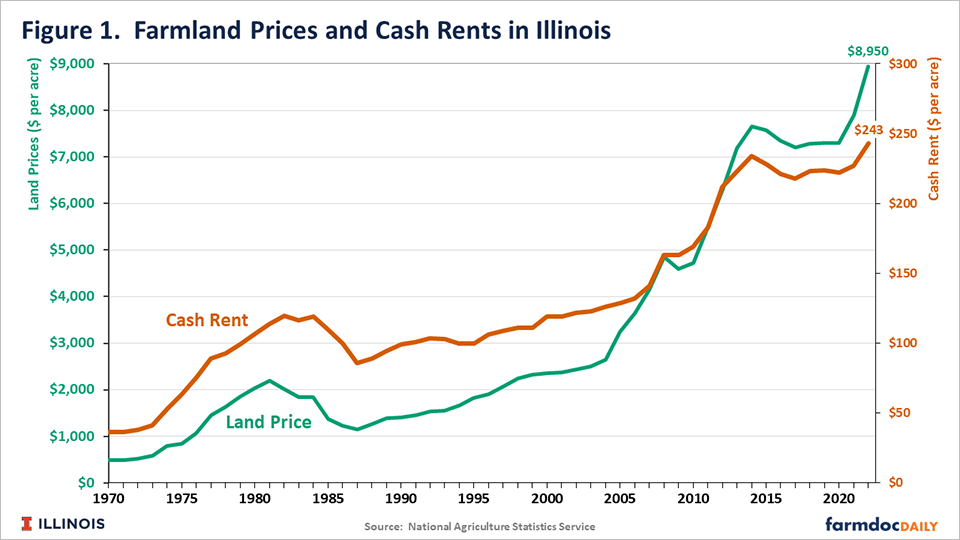

1. Farmland values in both the heartland and across the U.S. over the last 30 years have been on a stable and meteoric rise. See tables to the right and below. With a compound growth rate of ~5.9%, a huge incentive to keep doing what you are doing rather than to change.

Illinois Farm Land and Cash Rent Inflation

Illinois Farm Land and Cash Rent Inflation

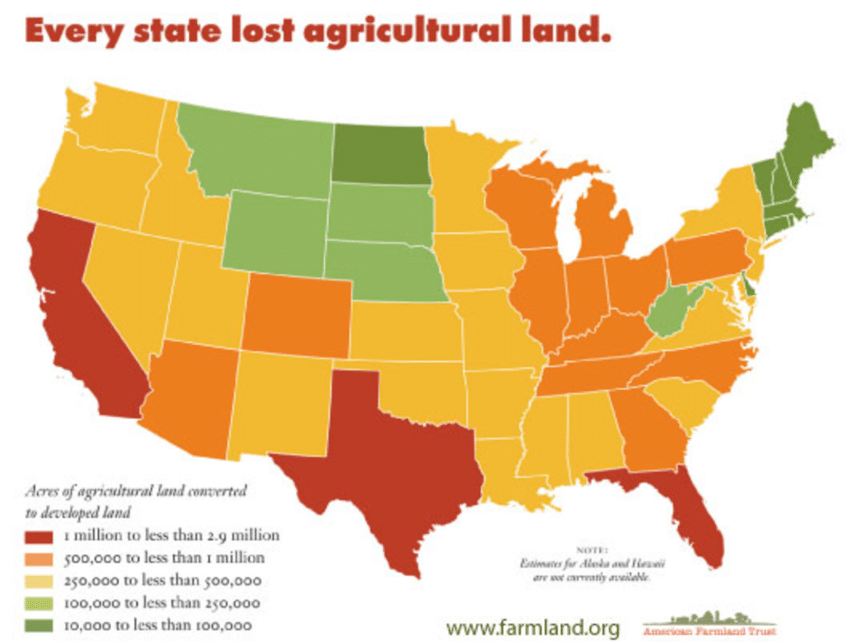

2. In the United States urban sprawl and alternative land uses such as solar & warehouse construction are causing a loss in farmland, decreasing supply and supporting higher farmland prices. It’s a sea of land loss across the U.S. With decreasing supply of land, the prices for existing farmland rise. Many farm owners, especially those near urban and suburban centers view development as their highest and best-use option for land value, rather than changing how they farm their land.

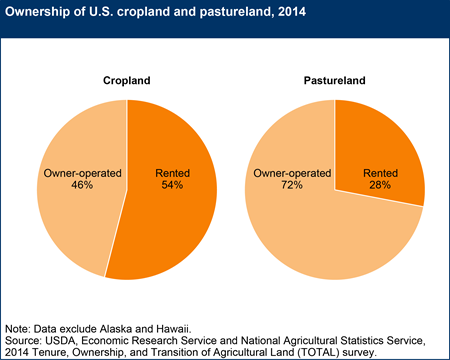

3. 54% of U.S. cropland is leased, and that number is growing. Land leasing is the relief valve for landowners retiring at an increasing rate or absent landowners still wanting to hold onto the farm. The only way to leverage higher land values is to raise rents. And to raise rents means only leasing the farm to a smaller number of operators that can support those rents due to their scale. This creates inertia for absent landowners who do not want to rock the boat and change because they may only have 1 or 2 tenant options at the scale that can support higher rents.

How this trend disincentivizes regenerative land use change

The United States is home to some of the greatest farmland in the world. This is exactly why it is so hard to incentivize change. Why change when land values continue to rise all else equal? Even more, doing something perceived as different could threaten this golden goose.

It is incredibly hard for first-of-a-kind farms in new places trying new practices. If you are the only organic farm in a sea of conventional feedstock grain producers, you may be getting a premium on your grain, but you likely are not getting a meaningful premium on your land values unless your neighbors also transition to organic. This is largely due to supply and demand.

If your neighbors are growing conventional feedstock crops, your land value will be compared to theirs, not the organic farm in another county or state. In some cases, productivity (as measured by yield), can be lower on regenerative farms (ex. due to crop breeding limitations) than their conventional neighbors, and as such lower yields may be viewed negatively or as a weed problem, even if you have a crop premium. When the market is the equity in the land, change quickly becomes an outlier, and not a proof point.

Where does farmland value appreciation accrue over time? It accrues primarily to landowners, not farm operators. As land prices increase, commodity prices and margins need to keep pace to cover the lease rates (largely determined by target return rates on property values - referred to as cap rates). 54% of cropland is leased in the U.S. meaning, the land value is linked to what farmers are willing to rent for. Rents are a derivative of farm operator profitability, but in many markets, land access is competitive only between a few of the largest players who can afford competitive cap rates.

We should absolutely work with the largest farms to help them grow and increase their impact. While these farmers are large, they are certainly not prone to large risks, and one of those risks is changing practices. They got large to serve the need of managing more land and providing jobs to their communities. So to change, they have to do so slowly over time without risking their landlord and community relationships. Going from conventional tillage to organic-no-till with roller crimped cover crops before planting corn is going to take time and some failures on a trial plot scale for these farm operations to transition unless they get capitalized at the operational level, rather than at the farmland equity level.

How we solve these headwinds:

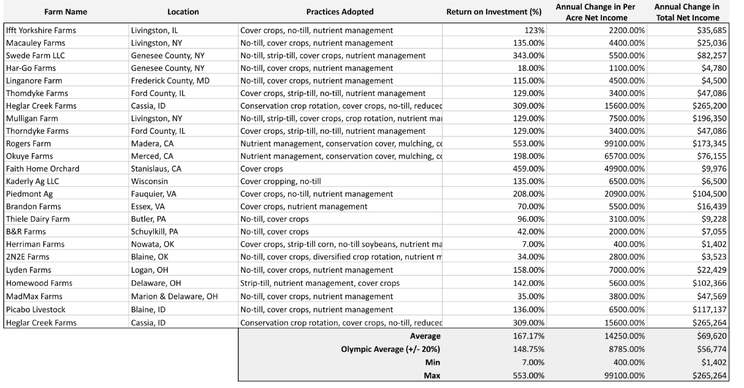

Land values are not going to come down meaningfully with an inflating agricultural economy, but commodities will go down (and up) unpredictably, causing stress on farmers that lease or are highly levered with debt. While regenerative farms may be more profitable as seen below, there just aren't enough farms yet in alternative markets to create trust from landowners. There are hotspots where organic and regen practices have taken hold; we need to learn from those areas, because reaching a local minima of adoption flips this dynamic on land values to some extent, but usually to the more expensive side. This creates an additional catch 22 with land affordability.

American Farmland Trust, ROI on regenerative practice adoption

We can cut through these headwinds by investing in the growth of farm operations directly to pursue a higher value offtake mix which can often mean better practices. This can be achieved through buyers that purchase based on practice standards that demand a premium (e.g. organic) or through new crops with higher margins and revenues (e.g. tree nuts or timber). With well- structured equity, debt, and incentives at the operational level, we can cushion the transition to higher value offtakes without leveraging the land values, which cannot be leveraged. This is due to an increasing inability to leverage land values at the operational level due to leasing. Landowners that lease have a limited ability to leverage their land value for another operation’s P&L, and farmers that own land can only lever their own land so much to improve another landowner’s farm’s soils that they are leasing. We must rely on the merit of more profitable farm operations to underwrite these transitions.