Growing Agroforestry into the Mainstream

Guiding Questions:

Who is drawn to agroforestry? Why?

Why agroforestry, here and now?

What does agroforestry adoption look like across a population?

What can The United States learn from agroforestry in South America?

What does agroforestry need to grow, replicate, and scale in the United States?

Introduction

Agroforestry is the incorporation of trees and farming: trees on farms on purpose. The benefits of agroforestry accrue over a long time horizon, and the archetypical agroforestry-interested person is generally open-minded, somewhat hardworking, doesn’t stress very much, and is willing to speak out if something doesn’t seem right. These traits generally map onto the “innovator” or “early adopter” phases of technology adoption. But in different countries, agroforestry is at differing stages of adoption, given diverse geopolitical and biogeophysical climates. Interestingly enough, we can tie together personality, innovation, and general political orientation in the lens of how interested a society is in trees. If we are to advance agroforestry, understanding this axis is fundamental.

Questioning farming?

Questioning the absolute optimization of land use for food production is novel. Questioning corn is sacrilege in Iowa. Raising sheep and cattle in Great Britain is culture. Favoring long-term ecological stability over the option to grow food today is met with resistance, because true food security is an anomaly. 300 years ago, nature was the antithesis of civilization. Wolves preyed upon our livestock, and Little Red Riding Hood was more than a fairytale. Especially in cold climates, the forest didn’t produce many calories, and true famine was all too familiar. Food security and public health were nearly synonymous, and ecology was an afterthought, if that. Hunger generally destabilizes a society, but today hunger and acute malnutrition and not caused by insufficient food production, but are a consequence of inadequate food distribution. At the turn of the millennium, we produced enough calories to feed 8 billion people. Given that we now have enough food, we can rethink and change how we produce it. We now have a license to optimize for food quality and a higher-order stewardship of our landscapes. Agroforestry moves us towards a manageable equilibrium of diversified, integrated land use that yields staple foods, fiber, fuel, and ecosystem services.

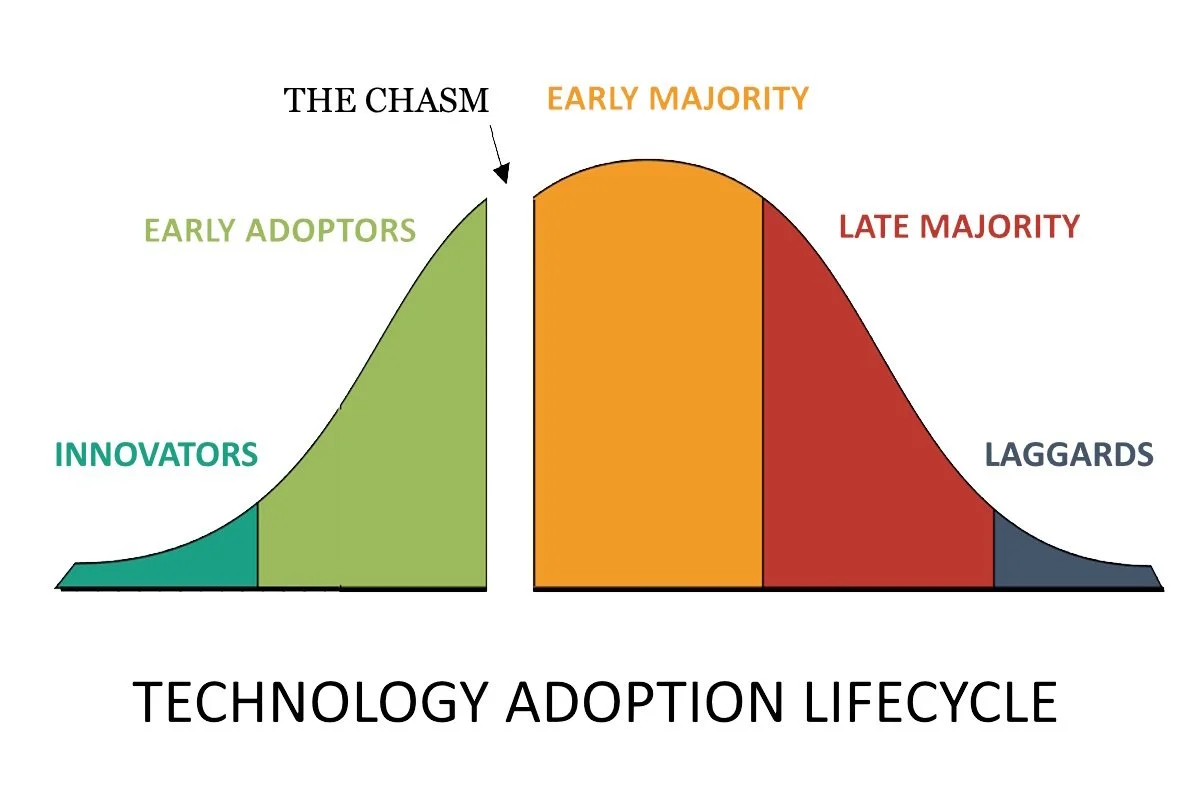

The Technology Adoption Curve

New technologies are met with open arms by some and strong resistance by others – and all emotions in between by the rest of us. Technology adoption is normally distributed for the most part, on a bell curve. The innovators are first users, followed by the early adopters, the early majority, the late majority, and finally the laggards. Agroforestry largely falls into the domain of the innovators, in the left tail of the curve. However, there are regions of the world, namely Latin America, where agroforestry is a golden child of the early majority. Though anecdotal, I can see this in the personalities of those that practice it – and my sample size is robust. Though I do not yet have empirical data to back this assertion up, I can see in the personalities and dialogue of Argentines, Paraguayans, and Colombians that agroforestry is synonymous with pragmatism rather than compromise. Those of the early majority are planting trees. This is to say that trees are seen as a compliment, and not a sacrifice to Gaia. Given: some of this has to do with the climate in South America, but not all of it.

The Political Spectrum of Agriculture

Is ecology left-wing? Kind of, but not all the time. Agriculture, land use, and relationship with nature map onto a political spectrum reasonably well. This foray may or may not be necessary for the sake of today’s op-ed, but humor me if you would. On the far left – Rousseau to a fault – is forest anarchism. Slightly less far left is permaculture. Left of center we see the word agroecology, often grouped with agroforestry. Silvopasture, a subset of agroforestry, seems to be slightly left of center. Organic grain and pastured livestock farming range from just left of center to slightly right. A corn-soy-wheat crop rotation falls right of center, with continuous corn to the right of that. Razing the amazon to grow corn and soy to feed pigs is pure Hobbessian, high-discount-rate farming. For what it’s worth, adaptive multi-paddock grazing (holistic planned grazing) might be the most politically agnostic form of protein production. We should make it clear that these are not rigid categories: open-minded, innovate grain farmers are plentiful, and narrow-minded ecologists definitely exist.

This spectrum in part overlays onto the technology adoption curve and personality dimensions that contribute to political orientation. “Society is stable because of tradition” is a conservative idea. The downside of blind adherence to tradition is that we ossify in the past: the gift of those that exhibit trait openness is to ensure that our institutions evolve with the times. Conservatives in turn stop the leftists from tearing down society. “Stability is great. Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.” The left is tasked with innovating, and the right adapts the once-creative endeavors into a pragmatic, functional, integrated cog of society. Components of agroforestry, once thought radical, will normalize.

How does agroforestry show up in society?

In the United States and Europe, agroforestry seems to be a domain of the ecology-forward Rousseauian left. Less common are the questions: “How do we scale this?” and “Where does the rubber hit the road?” In South America, the agroforestry room is full of agronomists. Dialogue is that of production and profitability. I recently spent five days at the Argentine Silvopasture Congress and International Silvopasture Congress in Uruguay. Of 500 total attendees I was the only agronomist from the United States, and fortunately I studied in Buenos Aires and speak fluent Spanish. The doors that language opens! The South Americans take it as a given that agroforestry and silvopasture are inherently more biodiverse and yield ecosystem services as a positive externality (co-benefit). That conversation has been had. The more important facet of useful trees is that they improve farmer livelihoods. The pioneers of silvopasture have dozens of anecdotes and a plethora of empirical data showing that complex multi-story farming lifts people out of poverty. 30 years ago, silvopasture was an idea. Extension agents, private agronomists, and farmers ran it through the gauntlet, and the data is in. Silvopasture has legs. Can we transcend the need to further demonstrate that trees are ecologically good?

How do we see agroforestry maturing in The United States?

As agroforestry matures in the United States, learning from South America will accelerate the process. “Yankees,” as we are known in South America, are notorious for projecting our ideals onto other cultures, for better or for worse. It’s now time that we learn something from the Southern Cone. “Tech Transfer” is the abundance-oriented inter-societal dissemination of knowledge. The nature of silvopastoral relations is one of abundance: both the pioneers and the younger agronomists are incredibly approachable. As early adopters, they’re open minded, and they’re also friendly. They’re excited to help us bring silvopasture online in the United States. The future of agroforestry and silvopasture is bright, and both South and North America have a lot to look forward to. Here I’ll include some actionable next steps:

Plant trees in straight lines – Efficient management does not need to compromise ecology. A hired tractor operator should not be asked to drive on eggshells. Straight lines can include inflection points, and can largely align with landform and or against prevailing winds.

Simplify species composition – By all means, include biodiversity, but ensure that such tree placement is pragmatic and aligns with production goals.

Emphasize markets – An agroforestry system is often a complementary enterprise that produces salable goods such as wood products, nuts, and fruit. Goods are only salable if a buyer is present and accessible.

If our objective is to scale and replicate agroforestry, we should implement tree systems that are generally accessible to more farmers and landowners. Regardless of ecological intent and ethos, agricultural systems that create cultural momentum are those that will grow.