Chestnut Pricing and Markets

Who buys chestnuts, how do they buy them, and how much are they willing to pay?

Summary:

People like chestnuts, and chestnuts have good branding.

There are fewer chestnuts than there are chestnut-eaters, which raises price.

Prices are still variable, as they always are. More marketing leads to higher prices.

Sell whole nuts to East-Asian immigrants and value-added products to others.

The chestnut industry will continue to evolve.

If you would like to plant chestnuts, learn more here.

What are chestnuts?

Chestnuts are a staple crop the world around. They’re a flavorful starch, much like a plantain or a nutty sweet potato. From whole roasted nuts to flour and pancakes, chestnuts will fill you up and never let you down. Chestnuts are generally a profitable crop for farmers, but there’s nuance here.

Chestnuts are a long-term asset. Chestnuts grow on large trees, and compared to corn they reduce soil erosion, improve water quality, and increase biodiversity for decades. This makes them appealing to ecology-forward land managers and NGOs, on top of their general profitability. The long-termism of chestnuts also creates a barrier to entry for growers. Farmers that plant the trees must wait 6-8 years for a harvest, and 10-13 years to break even. As a result, chestnuts are currently supply constrained: more people want to eat them than global supply can satisfy, and prices are stable and reasonably high as a result. One of the hot topics in the chestnut industry is price. What can we expect price to be? What should we plan for? Price largely depends on which market we’re selling into, and we should understand the associated levers.

What is the sale price of chestnuts?

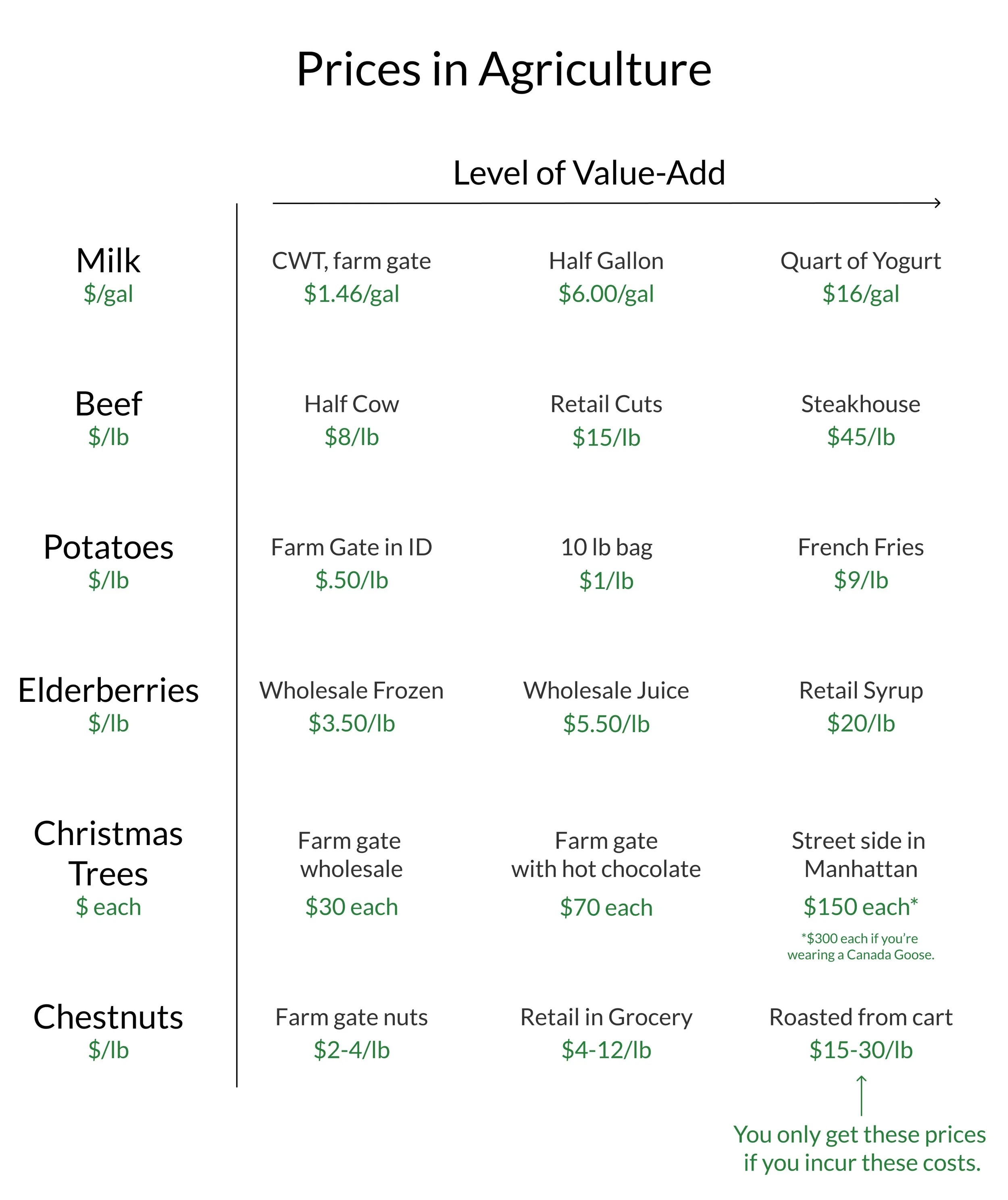

We’ve planted roughly 2,000 acres of chestnuts, both for our own business and as a contractor for other farms. We’re inseparably invested in the crop, and creating economic stability for both ourselves and our partner farms is core to our business. Before we plant trees for clients, we run an analysis for each farm, showing forecasted costs, revenues, yields, and labor assumptions. We communicate the clear distinction between selling wholesale and selling retail. As with any agricultural product, the closer we get to the end consumer, the more value we capture and the higher our sale price will be. Farming is unique in that it presents a gradient from soil-centric operations to people-oriented marketing. Different farmers focus on different facets of this value chain.

A farm business’ ideal state is selling at retail prices while maintaining farm-gate costs. This is rarely attainable, and that’s okay. Retail prices require distribution and marketing, which require our time, resources and margin. The old adage is to “cut out the middle man.” But only cut out the middle man if you’re up for taking on his workload. Sometimes that’s worth our while, and sometimes it isn’t something a farmer wants to do. All things considered, the most profitable farms usually take on a larger percentage of the value chain.

Examples:

Route 9 Chestnut Cooperative sells direct to consumer. They were largely a first-mover in the chestnut industry and sell out within 48 hours of opening their online store.

Asian grocery stores sell ready-to-eat bagged chestnuts for $7-20/lb, and frozen chestnuts for $7-14/lb.

The Great Chestnut Experiment sells roasted chestnuts at Manhattan farmers markets for $24 per lb. They maintain a presence in New York City.

Who Buys Chestnuts?

The largest buying group of chestnuts in The United States is Koreans in Los Angeles. The second largest buying group is Koreans that are not in Los Angeles. Veteran chestnut growers are quick to explain that the most significant buyer demographic is East Asian immigrants that do not speak English as a first language: Koreans, Chinese, and Japanese. Bosnians and other Balkan immigrants are the second largest buyer demographic, followed by those from other chestnut cultures such as Turks, Italians, French, and Spanish.

Chestnut growers will candidly tell you that the people who grow chestnuts usually don’t look like the people that buy chestnuts, and they often don’t speak the same language (literally). Julie Richards of Ohio Chestnut explains that connecting with East-Asian buyers isn’t super complicated: find churches and community centers near you, and reach out in early September. Many of them are excited to buy chestnuts. Cross-cultural outreach can be intimidating for some, and can sometimes require some persistence. But the sales and marketing initiative that justifies a higher sale price is the largest economic opportunity for a chestnut grower. Chestnuts are only profitable if you go out and sell them. There is a persistent narrative in the chestnut space that East Asian and Bosnian buyers will find you as a chestnut grower, show up at your farm to hand harvest the nuts themselves, and beg you to take their money. New growers should not assume this to be true, and will need to engage in persistent marketing. If they find you first, all the better.

Chestnuts for English Speakers

Among Americans that speak English as a first language, chestnuts generally have excellent branding. You’ve likely heard about The American Chestnut, and felt the nostalgic allure of chestnut roasting on an open fire. This is for good reason. Chestnuts have fed rural people for thousands of years, and are generally considered to be a health food: nutrient-dense and slow to break down. Holiday market goers will enthusiastically buy a cone of roasted chestnuts. But outside of adventurous cooks over Thanksgiving and Christmas, this demographic is unlikely to buy whole fresh chestnuts. For the health-conscious consumer, chestnuts are an ingredient. Chestnut flour, pancake mix, granola, cookies, and breads are largely seen as the route to mass-market chestnut consumption.

Supply, Demand, and Competition

Demand is currently outpacing supply, leading to high prices in certain markets. If we look to the future, we should dig deeper via Porters 5 Forces of Competition. An in-depth industry analysis from the point of view of a grower would show:

Low buyer power due to seller capacity to sell direct. Buyers are many and disaggregated.

High supplier power due to relatively few market participants.

Large number of substitutes: any high-quality starch. Chestnuts are an expensive carbohydrate.

Low existing competition: There are 10,000 acres of chestnuts in the United States, compared to 409,000 bearing acres of pecans.

Moderate threat of new entrants: the number of acres of chestnuts farms is expected to double over the next decade, and imports are persistent (though often fumigated).

Imported chestnuts are a substitute for some, existing competition for others, and theoretically a new entrant as well.

The Chestnut Industry will Evolve

Chestnut prices and market dynamics will change. Growing Chinese chestnuts commercially in the United States is only just coalescing into a new industry, and chestnut producers are evolving from niche hobbyists into professional growers. Chestnuts are not a mature market (not perfectly competitive), meaning that prices have not stabilized and products are not standardized. As a grower, you can often set your own price, and sell any variety of chestnut value-added goods. Apples and pine trees, by contrast, benefit from predictable prices in part because they are saturated at every level of the supply chain and at every level of value-add. Even though market fluctuations exist, we can always find a buyer or a supplier of wholesale apples, pecks of apples, apple juice, apple sauce, apple pie, and dried apples. Likewise with standing timber, logs, wholesale lumber, pre-made stairs, and cabinets. With this mature market comes minimal opportunity to make money selling apples and pine lumber at any level of value-add. It’s hard to beat Home Depot at selling 2x4s and ugly sheds. Prices of chestnuts vary to a greater extent than apple and lumber pricing, and there is open opportunity to add value. As the chestnut industry matures, the price of unprocessed nuts will likely compress, encouraging growers to add incremental amounts of value.